Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

Chapter 1 — Patterns in the Quiet

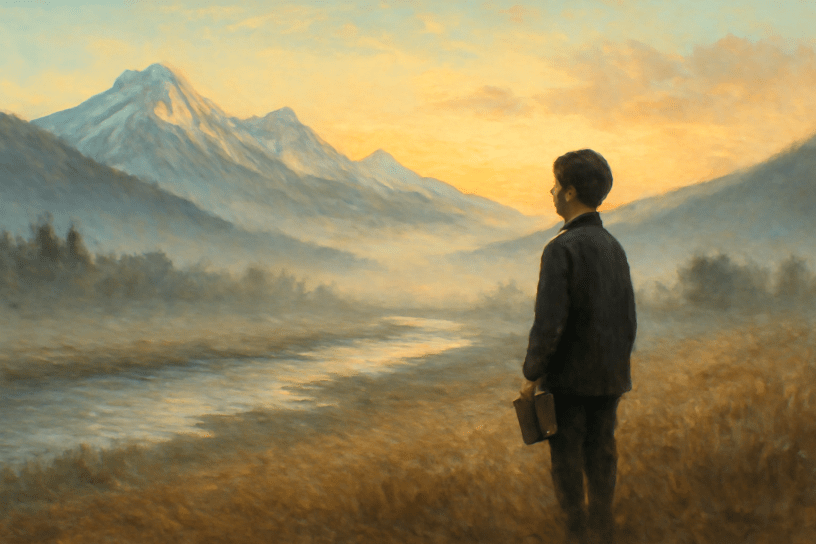

I was born in the Altai Mountains, in the fold between stone and silence. But it wasn’t a lonely silence—more like a quiet companion. The mountains didn’t shout; they waited. The air was crisp, the sky endless, and even as a child, I felt that everything around me had its own kind of memory.

I grew up on a collective farm. It was a small place, practical and simple. We didn’t have much, but we had enough, and no one went hungry. Life moved with the seasons: planting, tending, repairing, harvesting. The routine could seem dull to some, but to me, it was a world full of small discoveries. I had the freedom to explore, to take things apart, to ask questions that no one scolded me for asking.

My father, Pyotr, was the village mechanic. He was patient with machines, and even more patient with me. He’d let me watch as he repaired engines, gearboxes, anything that turned or hummed or rattled. “Every tool has its voice,” he once said. “You just have to know how to listen.” That stayed with me.

My mother, Valentina, ran the library. She had a calm way of managing both people and shelves. Our home always had books on the table. Most were assigned literature or scientific journals from the Soviet programs, but a few were older, more poetic, or quietly set aside for those who asked. I read what I could—even if I didn’t understand it all yet.

Soviet newspapers were always around too. They were dry, yes, but steady. You could read them with a cup of tea and feel like the country was moving somewhere—even if you weren’t sure exactly where. And they didn’t lie the way people do now, with noise and spin and contradiction. Back then, if a factory reached 112% of quota, it was printed just like that, with a photo of the workers smiling.

I was drawn to patterns. In the clouds, in the shape of snowdrifts, in the pauses between wind gusts across the steppe. I began keeping a notebook of these little repetitions—when certain birds arrived, how frost formed on different surfaces, when machines failed most often. It wasn’t science yet, but it was observation. Careful watching.

By ten, I’d taken apart everything that stopped working. Radios, lamps, clocks. Some I fixed. Others I turned into new things. My father allowed it so long as I didn’t touch the few tools he called “for real work.” My proudest achievement that year was rewiring an old crystal radio to catch long-distance broadcasts. I’d lie awake listening to music and voices from faraway republics. The signal came and went, like hearing someone speak across a windy field.

The first time I read about magnetism—in an issue of Yunyy Tekhnik—it struck me like poetry. Invisible forces, acting at a distance. That made sense to me. I felt like the world had always been whispering those rules, and I was just now starting to hear them clearly.

No one told me to become a scientist. It wasn’t a choice made at a single moment. It was a direction, like a slope in the land—you don’t notice you’re following it until you look back and see how far you’ve come.

Chapter 2 — The Ridge and the Fire

One summer, when I was perhaps fifteen, I wandered farther than usual. The ridgelines in Altai had always drawn me in—stone shoulders layered like waves in a frozen sea. I packed bread, salt, a small pot, and went out alone with my bedroll and notebook. It wasn’t unusual for me to camp solo. My parents didn’t worry much; boys there were expected to know the land like they knew their own hands.

I was three days out when I heard the singing.

Low and old. Not melodic in the usual sense—more like chanting, or humming dragged through gravel. It came in waves, like the wind but steadier. I followed it in silence, stepping carefully through the brush until I reached a high ridge clearing, half-ringed by pine.

There, by firelight, sat five old men. They were drinking something thick from a shared wooden bowl. Smoke hung low over the fire, and their voices moved together, dipping in and out of harmony like they were pulling something from the night itself. I didn’t understand the words. Later I would learn it was Altaian—an older dialect still kept alive in pockets of the mountains. But even then, I could feel that it wasn’t just song. It was doing something. To the air. To the sky above.

I crouched behind a pine, holding my breath.

I must have fallen asleep in the bushes. I don’t know how long I was out—maybe an hour, maybe until dawn. But I awoke to sunlight and shouting.

The men were furious. Not at me—at each other. They were standing around the ashes of the fire, gesturing sharply, arguing in fast, rough voices. One of them kept repeating a word I didn’t recognize, then suddenly switched to Russian:

“Stolen… stolen… but not by us!”

I didn’t understand. I stayed completely still, hidden by the tree’s thick roots. My heart was pounding. At first, I thought they might be speaking of spirits or symbols. But then another part of me wondered if something physical had gone missing. A tool? A relic? Something sacred?

And if they found me—some barefoot teenage outsider in the bushes—would they believe I hadn’t taken it?

I started inching backward, slow as I could. Then faster. Then I ran—branches lashing my face, heart hammering in my chest, fear pounding louder than my steps. I didn’t stop until I reached the river.

I never told anyone. Not my father. Not even my closest friend at school.

But something changed in me after that.

Over the following months, I felt different. Not haunted—just… tuned. More aware. The trees gave off moods I hadn’t noticed before—some days sharp and restless, others slow and watching. The sky felt denser on certain mornings, like it held back something not ready to fall. I could tell when a storm was coming hours before the clouds formed. My hearing sharpened—not in volume, but in what I noticed. I could hear silence. Or the shape of it.

I didn’t try to explain this to anyone. I wasn’t even sure I could. It wasn’t mystical. It didn’t feel like a gift. More like a shift. Like a gear that had quietly turned while I slept in that clearing, and now I heard the world slightly out of phase with the people around me.

It wasn’t frightening. Just different.

And once you begin noticing that kind of difference, it’s very hard to stop.

Chapter 3 — Farewell to the Altai

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

Chapter 3 — Farewell to the Steppe

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

Winters were long in our corner of the world, and school days could feel even longer. We trudged through snowdrifts to a classroom where the coal stove only warmed the front row. We learned mathematics in our coats, history in our mittens, and wrote essays with fingers too stiff to curve the letters cleanly.

But summers made up for it. Time flew then—working the fields, riding to distant pastures on wiry horses, bringing back hay or armfuls of leafy feed for the cows. The scent of fresh-cut grass, of saddle leather and sun-warmed soil, still lingers in my mind. We’d rise early, work until the sun hovered low and golden, and end the day tired, dusty, and laughing over sour milk and black bread. That was life. Simple, but rich in its own way.

And then—like that—it was time.

The summer I turned seventeen, the letter came. I had been accepted into a technical university in Sverdlovsk. I had applied quietly, through a teacher who believed I could go far if I just got far enough away. I hadn’t thought much would come of it, but here it was—an official acceptance, with a place reserved for me in the engineering faculty.

My parents didn’t say much at first. My father nodded and went to the shed to check something in the toolbox. My mother held the letter like it might crumble if she blinked.

But then they began to prepare.

They packed my bag with everything they could think of. Homemade wool socks. A small tin box with needles and thread. A thermos. A battered volume of Lomonosov’s writings. My mother tucked in a bar of chocolate, wrapped in brown paper. “Train food,” she said, trying to sound cheerful.

My father came back from town with a train ticket already bought. Sverdlovsk. One way.

When the day came, we walked together to the bus stop that would take me to the train station in the next town. My mother hugged me so hard it knocked the breath from me. My father shook my hand, then pulled me into a sudden embrace, clapped my back twice, and let go before he said anything he couldn’t unsay.

They were proud. But it was pride with tears behind it.

“Don’t forget who you are,” my mother said.

“And don’t come back a fool,” my father added, with half a smile.

I boarded the bus with my bag, my books, and everything I had been. Through the window, I saw them standing there long after we pulled away, two figures growing smaller against the wide sweep of the fields.

That was the day I left the steppe.

Chapter 4 — Four Days Across a Continent

I boarded the train with my satchel slung over one shoulder and my mother’s bread still warm in my bag. The station at the edge of our district was small—just a long concrete slab with a rusted sign and a few men smoking under the roof. I found my carriage near the end of the train and climbed aboard.

It was a platzkart car—third class, open, crowded, alive. No doors between compartments, just rows of bunks and passageways that folded into one another like pages in a book. Everyone could see everyone. Privacy was something you left at the platform.

The train creaked, groaned, then slowly pulled away, gathering rhythm like an old musician picking up tempo. I found my seat by the window, pushed my pack beneath it, and opened a book I had brought from home. I tried to read, but my eyes kept drifting out toward the disappearing fields, toward the receding silhouette of everything I had known.

We rolled through birch forests and coal towns, across rivers wide as memories, past villages where children chased the train like it might carry a message from somewhere better. The countryside blurred into a moving canvas.

My fellow travelers were a mosaic of the country. Laborers, factory men, teachers, conscripts, a nurse with two heavy suitcases, and a grandmother who peeled apples with a paring knife and handed slices to anyone who smiled at her. Conversations bloomed like flowers between bunks—loud, funny, sometimes absurd. Men told stories of factories where no one worked but everyone got paid. One man swore he’d once seen Lenin’s ghost in a vodka warehouse. Everyone laughed, especially him.

Someone played a battered guitar. Someone else shared dried fish and cucumbers wrapped in newspaper. The smell of tea, boiled eggs, and engine oil filled the car. It was noisy, yes—but cheerful. The kind of cheerful that doesn’t need permission. Everyone seemed to understand that for these few days, we were all neighbors.

At night, I lay on the upper bunk listening to the rhythmic metal lullaby of the wheels—clack-clack, clack-clack. The sound settled into my chest like a second heartbeat. I didn’t sleep much, but I didn’t need to. There was something comforting in the motion, in the low hum of voices rising and fading, in the smell of iron and fabric and shared humanity.

We passed through Novosibirsk, then Omsk, then Tyumen. The days blurred, but as we drew closer to Sverdlovsk, something shifted.

I became restless. Then more restless still. It wasn’t fear—not exactly. It was as if my soul began to pace before I did, unsettled by something it sensed ahead. I read, then put the book down. I stared out the window, then turned away. I didn’t know what was waiting for me, but part of me already suspected it wouldn’t be simple.

By the fourth evening, the conductor walked through with a shout:

“Sverdlovsk next!”

And just like that, the train that had been my whole world for four days became a memory—left behind on the tracks as I stepped into the next part of my life.That was the day I began to become something else.

Chapter 5 — Platform Decision

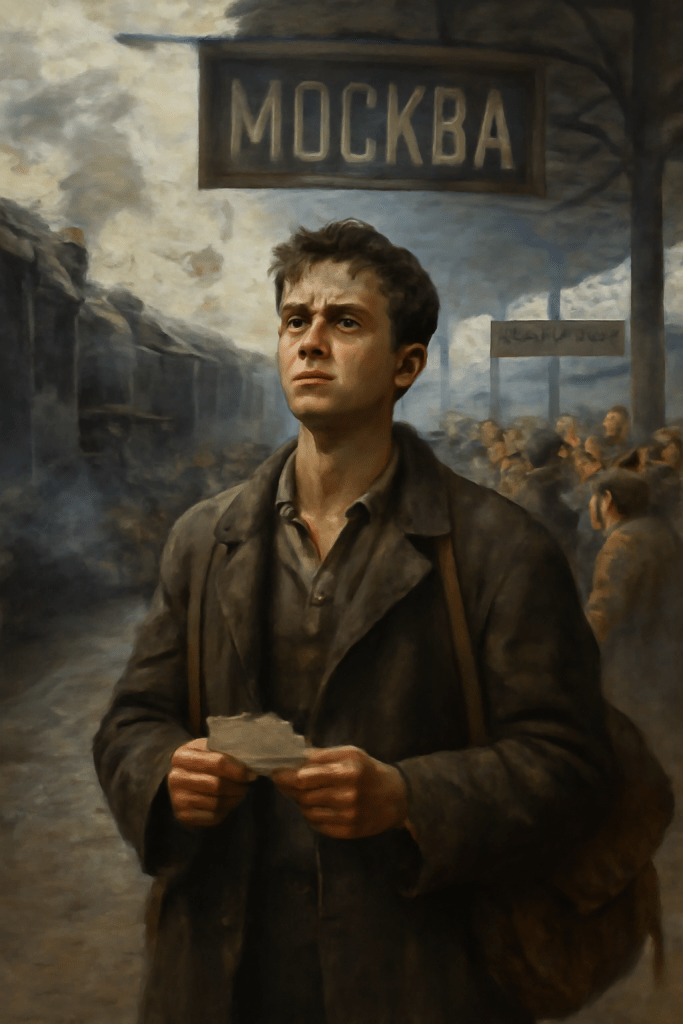

Sverdlovsk. The platform hissed with steam and clattered with boots and bags. I stepped off the train into a wall of noise and motion—announcements echoing overhead, families shouting greetings, soldiers rushing to find their units, vendors calling out prices for boiled eggs and kvass.

It should have felt like arrival. Like destiny unfolding. But it didn’t.

I stood there with my bag over one shoulder, clutching the documents I’d carefully guarded for four days, staring out across the crowd. People moved around me in rivers, but I felt like a rock dropped into the middle—still, foreign, uncertain. Something didn’t sit right.

It wasn’t fear. It was a kind of instinct. Like my feet were planted in the wrong story.

So I did what every good Soviet student was trained not to do: I changed the plan.

I walked straight to the ticket window, stepped up without a word, and pushed a few crumpled rubles across the counter.

“One ticket,” I said.

The clerk barely looked up. “Where to?”

I didn’t hesitate.

“Moscow.”

There was a pause—maybe she expected me to say it again. But I didn’t. I just stood there with that same still feeling in my chest, waiting for the paper that would carry me toward something that hadn’t been written yet.

She stamped the stub, slid it under the glass.

Platform 6. Train departs in twenty-three minutes.

I turned around and didn’t look back.

Chapter 6 — Moscow: The Shockwave and the Spark

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

I stepped off the train at Kazansky Station, and it hit me like a shockwave.

The air was thick with coal smoke, diesel, and the scent of wet stone. Crowds surged in every direction—soldiers, students, babushkas with baskets, porters shouting over the hiss of brakes. The station’s vaulted ceiling echoed with announcements and the clatter of boots. I stood still, bag in hand, watching the river of people flow around me.

And yet, in my chest, a strange warmth bloomed.

I had no map, no address, no plan. Just a list of technical institutes scribbled in my notebook and the reckless certainty of youth. I was seventeen, and Moscow felt like the center of the universe.

I wandered out into the city, past the red stars atop the Kremlin towers, the endless avenues, and the towering buildings that seemed to scrape the sky. The city pulsed with energy, and I was caught in its rhythm.

At a street corner, I spotted a small kiosk with a sign reading “Справочное бюро”—the information bureau. Inside, behind a glass window, was a bulletin board covered with notices. I pressed closer, scanning the list of technical universities:

- Moscow State University (Lomonosov)

- Bauman Moscow State Technical University

- Moscow Polytechnic University

- Moscow State Mining University

- Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT)

The names blurred together as I tried to make sense of my options. Each represented a different path, a different future.

I took a deep breath, the city’s energy coursing through me. I didn’t know where I would end up, but I felt certain that I was exactly where I needed to be.

I knew where I’d start.

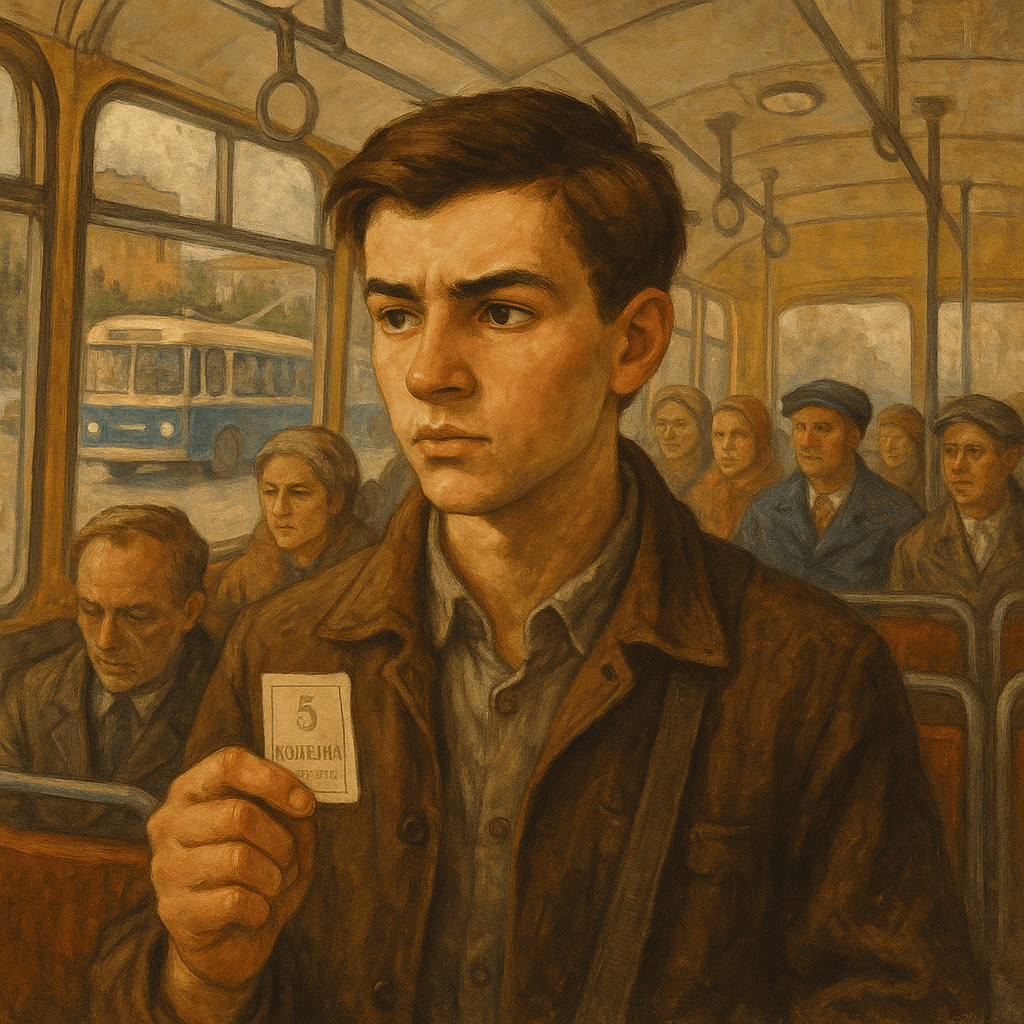

Some part of me probably knew all along—I would end up at Bauman. Still, I wanted to leave it to fate, just once. So I closed my eyes, pressed my finger to the folded paper where I had scribbled my shortlist, and when I opened them—

Bauman Moscow State Technical University.

That was it.

I didn’t hesitate. I walked to the corner kiosk, asked for directions in my best city accent, and exchanged two coins for a 5-kopek bus ticket. The ticket felt like a passport. I rode through Moscow’s wide boulevards, past parks and factories and long gray buildings, the city outside flashing like scenes from a film I wasn’t in yet.

When I stepped off the bus and looked up, there it was.

Bauman. It didn’t look like a school. It looked like a fortress of science—tall, proud, and slightly intimidating. The kind of place where ideas had mass, and equations walked the halls in boots.

I stood there for a moment, letting the sight sink in, then turned to a boy around my age who looked like he belonged there. I pointed and asked quietly, “Acceptance office?”

He didn’t answer right away, just tilted his head, looked at my bag, and smiled.

“First time?”

I nodded.

He pointed down a long row of steps. “That way. Follow the posters.”

And so I did.

I didn’t know what would happen next. But as I walked toward the doors, I felt something settle in my bones—not fear, not excitement. Just readiness. The kind of feeling you get when a long path suddenly becomes a hallway.

Chapter 7 — Forging Steel

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

The Soviet education system was not built for comfort. It was built for ideological warfare—a national engine to mass-produce prodigies, scientists, engineers, chessmasters. It reached into every corner of the Union, even the forgotten villages in Siberia, and pulled children upward by force if necessary. It didn’t ask whether you wanted to grow—it demanded it.

Unlike in America, where education is a path left open but not insisted upon. There, each child grows—or doesn’t—depending on family, surroundings, luck. It creates brilliance, yes, but from a narrower pool. A lottery of talent, not a harvest.

In the USSR, they tried to shape every child into steel. Then, from that steel, they chose their swords.

I tried to become one of those swords.

But it wasn’t as simple as walking through a door and being sharpened.

My exam scores weren’t perfect. Not bad—but not enough to place me among the top-tier applicants. Village schools didn’t prepare you for city-level competition. We learned what we could, with the teachers we had. But compared to the boys from Moscow, Leningrad, even Novosibirsk, I was a farmhand with a slide rule.

Because of that, I wasn’t given a stipend. No dormitory either. I was officially accepted—but not supported. In a city like Moscow, that meant one thing: sink or swim.

So I swam.

I found night work through a quiet word passed between desperate students. In the basement of one of Bauman’s administrative buildings, there was a boiler room. Enormous, black-bellied furnaces, always hungry. A handful of us fed them in shifts—shoveling coal through iron grates, sweat on our backs, soot on our arms, and steam in our lungs.

It was hard, physical work. But it came with two miracles: a small wage and a place to sleep.

We weren’t officially allowed to stay there, but the foreman looked the other way. He had once been a student, too. We laid out our coats near the warmest pipe, curled up on planks or sacks, and slept in the quiet rumble of the machines we kept alive.

And in the hours between classes and shoveling, I studied.

I brought my textbooks down with me. I used a crate as a desk. By the flickering light of an old lamp, I learned thermodynamics while sweating beside the boilers. I memorized equations with coal dust on my hands.

Other students slept in tidy dormitories. I slept next to the heartbeat of the university itself.

And that heartbeat nearly stopped.

It was early December. The frost outside was deep enough to crack pipes and stiffen doorknobs. One night, the gauges on the second boiler started to rise—fast. Too fast. One of the newer boys had overloaded the feed, and something was hissing inside the system like a furious samovar. Pressure spiked, and the floor began to shake. The pipes whined.

Someone shouted, “She’s boiling dry!”

The foreman wasn’t there. No one knew what to do.

No manuals. No diagram. Just noise, panic, and heat.

But I’d grown up fixing machines no one else could understand. I knew the sound of a metal wall reaching its limit. I grabbed a wrench, shouted for the others to clear the area, and started tracing the steam line back to its intake. One of the valves was jammed with slag, the pressure bypass stuck open, rattling.

I didn’t ask. I didn’t plan. I just moved.

Released the bleed manually. Jammed a rod into the safety drain. Used a rope and pipe handle as leverage to crank open a rust-frozen coupler. For ten terrible seconds, I thought it would explode in my face—but then the pressure started to fall.

The hissing eased. The floor stopped trembling. The emergency passed.

We stood there soaked in sweat and melted snow, blackened with soot like coal miners, staring at the quieting machine. It was alive again.

No one said anything for a long moment.

Then the quietest of the boys—the one who always mumbled his physics—said, “That… was a good repair.”

I didn’t feel heroic. I felt relieved. Exhausted. And strangely calm.

The foreman returned later that night. He didn’t ask questions. Just checked the system, then looked at me, nodded once, and walked away.

From that day forward, no one questioned whether I belonged there. Not even me.

The next morning, I was summoned to the dekan’s office—the dean of students. I washed up as best I could and made my way through the snow, still sore from the night shift.

I remember the light hitting my back as I entered his office—sun through dusty windows, cutting across filing cabinets and the smell of coal that still clung to me. The dean sat behind a wide desk, fingers steepled, expression unreadable.

He looked over his glasses.

“You’re the boy from the boiler room.”

I nodded. Said nothing.

He tapped a folder. “Your academic record isn’t bad. Village school, yes. But effort… substantial. And last night, well…”

He slid a paper forward.

“You’ve been awarded a stipend,” he said. “And a place in the dormitory—if you want it.”

I tried not to show it, but I must have smiled. Then I asked him a question most students would never dare.

“May I keep working in the boiler room, sir? At least until the season ends.”

He raised an eyebrow. Then gave a quiet nod.

“Good. It’s warm down there. And we need heat more than pride in winter.”

I worked that job until the spring thaw. By then, I had memorized the layout of every pipe and pressure valve beneath the university. I knew which coal bins cracked, which gauges lied, and which wrenches had the most bite.

The next year, the dean offered me something different: a position as a physics laboratory assistant.

No more soot. No more boiler burns.

Now I held voltmeters instead of shovels. I scrubbed instruments. Rewired connections. Reset timing coils. And sometimes, when no one was watching, I ran the experiments myself—twice, three times, until I could predict the numbers before the dial even moved.

I had become part of the machine.

But I also began to understand how to shape it from within.