Chapter 8 — Among the Machines

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

By my second year at Bauman, I no longer felt like an outsider sneaking through the cracks. I had a dorm bed, a modest stipend, clean clothes without coal smoke in the folds, and a job I no longer had to hide—assistant in the physics laboratory. I had crossed a threshold.

My days followed a rhythm: lectures in the morning, lab work in the afternoon, and equations into the night. I was tired always—but not the kind of tired I’d known in the boiler room. This was the fatigue of the mind—tangling with logic, teasing meaning out of formulas, testing instruments that were sometimes older than me.

The lab was not glamorous. Fluorescent lights flickered overhead. The counters were scratched. Some of the voltmeters still carried the Stalin-era serial stamps. But it was quiet, and it was mine.

I swept the floor, restocked components, coiled wires, soldered contacts, aligned lasers no one else wanted to touch. But I listened. I watched. I absorbed. When a senior student left an oscilloscope half-calibrated, I finished the job. When a professor muttered frustration at missing results, I rechecked the setup and left notes that he later cited in lecture.

I didn’t speak much—but I was noticed.

They say in Soviet science, there were three levels of recognition: ignored, tolerated, and quietly depended upon. I was reaching the third.

And in those long evenings—after the official hours, when the corridors fell quiet and the fluorescents buzzed like distant stars—I sometimes witnessed experiments prepared by advanced students and visiting researchers. They used unfamiliar instruments—some custom-built, others clearly imported. There were vacuum chambers, cryogenic vessels, frequency counters with labels in German or English. Machines that hummed with a precision I could feel more than hear.

I didn’t understand all of it yet. But watching those experiments unfold felt like glimpses into the future—my future. The air in the lab was different at night. Thinner. Sharper. Like it belonged more to time than space.

It was during one of those quiet evenings that I found a stack of journals—half-hidden in the locked cabinet behind the oscilloscope cart. Old volumes, worn and translated into Russian for internal use only. Western journals—Nature, Physical Review Letters, Applied Physics—smoothed and stamped for lab circulation.

The translations were dry, but the ideas inside burned.

I read them like a starving man. The language wasn’t poetic, but it was precise—each paragraph a window into something happening far beyond our borders. There were schematics I didn’t understand yet, vocabulary I had to cross-reference with battered Soviet glossaries, and experimental chains laid out with clarity I had never seen before.

These were not political documents. These were blueprints for reality.

I began to copy the diagrams into my notebooks. I traced the layout of interferometers, polarization filters, ion traps, cryogenic gates. I checked every piece against what we had in the lab. I followed the logic of their setups, comparing the instruments step by step—asking myself why this resistor was here, why that measurement was taken in this sequence.

It was like reverse-engineering the mind of the West—through circuits and particle paths.

Landau and Lifshitz had already cracked open my imagination. Kvantovaya Mekhanika, Volume 3 of their theoretical physics course, became my holy book. But these journals… these journals felt like news from another planet. One where science wasn’t just survival, but exploration.

Sometimes I stayed long after my official hours were done, simply looking—at our equipment, at the setups left behind after demonstrations or supervised sessions. The imported machines especially fascinated me. They stood out from our own stock—sleek, precisely built, labeled in English or German, humming with that strange foreign confidence.

I began studying their technical manuals—thick, folded documents translated into Russian, full of grainy diagrams and strange terminology. They were meant to assist trained technicians, but I treated them like scripture. I traced wire routes, marked calibration sequences, compared parameter settings to the physical layout in our own lab.

And one night, something shifted.

I looked at one of our ongoing experiments—an imported diffraction laser alignment test—and something just… clicked. I saw how the configuration matched the logic of the Western schematic. I followed the beam path in my mind, saw where interference would form, and where the error in our own setup was likely hiding.

For the first time, I didn’t just understand how the machine worked—I understood why the experiment worked.

It felt like hearing a foreign language and realizing that you could respond.

From that point on, the machines stopped being mysterious. They became conversational. Tools I could interpret. Extensions of thought made solid.

One night, I noticed something off in one of our laser phase-delay experiments—nothing critical, just a small misalignment in the mirror chain that introduced noise into the data. I had studied the manual enough to know what was intended. So I adjusted it.

Only slightly. Two degrees. A fraction of a turn. But enough.

In the morning, Bauman was in chaos.

Word spread that one of the imported instruments had been tampered with. There was no note, no authorization, no name on the lab log. The foreign-made alignment was no longer factory standard.

The building fell into a strange silence. Then came the whisper: spy.

Equipment had been sabotaged before—sometimes by jealous students, sometimes by political actors. In a Cold War institution, such things were never taken lightly.

Within an hour, all laboratory work was suspended.

The doors were locked. Faculty were summoned.

Then came the real storm. The rektorat—the university leadership—convened. The prorektor for science arrived, as did several professors with gray hair and state medals. And quietly, with no announcement at all, the Bauman KGB liaison appeared in the hallway. I didn’t know who he was at the time. Not yet. But I would come to know him well.

They questioned every lab assistant. They pulled files. Examined maintenance logs. Demanded names.

Then, someone found my notebook.

It wasn’t hidden—it was always on the bench, next to the oscillators. Inside were my diagrams. Annotated schematics from the translated manuals. Beam paths. Phase delay calculations. A whole series of notes correcting and suggesting slight improvements to existing setups—none of it destructive, all of it… precise.

The panic stopped.

I was called in—not with handcuffs, but with quiet formality. I stood in the corner of a meeting room where none of the chairs were meant for someone like me. No one spoke to me directly for several minutes. Then one of the senior physicists, a man I had seen only from afar, finally asked:

“You adjusted the alignment?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“It was off,” I said. “The output data was distorting at the second mirror.”

A silence fell. The prorektor narrowed his eyes.

“And you knew this… how?”

I told him about the manuals. The schematics. The readings. I explained what I had done—not to interfere, but to improve.

There was another long pause. Then a quiet chuckle.

“Not sabotage,” someone said. “Just a very curious assistant.”

That was the day I stopped being invisible.

Chapter 9 — Gorky Spring

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

After the incident in the lab, everything changed.

I was quietly promoted. No ceremony. No announcement. Just a slip of paper from the dean’s office confirming my new status: Senior Laboratory Assistant, Department of Experimental Physics.

It meant longer hours, better access, and my own key to the equipment storage room—a badge of trust. Professors nodded when I passed. Graduate students asked for help without condescension. I wasn’t a boy with coal dust anymore. I was part of the machine that taught others how to build machines.

But with that came something else.

A presence. An awareness. A sense that I was no longer just working under fluorescent lights, but under a second, invisible one. I felt it most in the pauses—when I lingered by the photocopier, when I borrowed manuals no one else requested, when I asked too many questions about imported parts.

They never said a word. Never approached. But I felt the outline of that attention around me like static. A watchful friend, they would have called it in hushed tones. Protective, maybe. Or patient.

Still—I remember one morning vividly. I stood in front of the mirror in the dormitory washroom, adjusted my collar, and looked at my reflection like it belonged to someone else. Then I shrugged it off—стряхнул с плеча—like a layer of ash.

Enough. For one day, at least.

I grabbed my coat and headed to Gorky Park.

The air smelled of thaw. Pigeons bobbed between benches. Children chased one another around candy wrappers. Somewhere a portable radio crackled with Viktor Klimenko. The river was still half-iced, but there were boats being readied at the dock like they believed in the sun.

I met up with a few fellow students—real friends now, not just lab mates. We sat on the low wall near the fountains and watched girls walk by in newly loosened spring coats. Someone passed around sunflower seeds and joked about starting a revolution just to get out of physics finals.

I didn’t say much. I just watched the birds circling overhead, listened to the laughter, and felt something rare and almost forgotten: lightness.

For a few hours, the city felt unguarded. The future paused in its long march. The world was vast again.

And for the first time in a long while, I let it be.

I remember that day like a pressed leaf in a book—light, vivid, whole.

The boys—my friends—waved to a group of girls by the promenade. They weren’t strangers; they were classmates from the chemical faculty. The kind who smiled politely in lectures, but now laughed with their whole faces in the spring air.

One of our group had brought his guitar. He wasn’t a great player, but that didn’t matter. He strummed the chords he knew, and we sang whatever songs came to mind—half bard tunes, half student anthems, all of it sincere. The kind of music that comes from people still young enough to believe in every note.

We sang. We laughed. We walked back together in the evening, the city glowing with orange windows and long shadows.

It was far, yes—from the park to our dorms across half of Moscow—but none of us cared. Our feet were light. Our hearts lighter.

That evening was a song in itself.

Chapter 10 — Return to Altai

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

In my final year as a student, I expected something to happen.

Not ambition exactly—more like readiness. I had done my part. I had stayed late, solved what others overlooked, kept my head down when I had to and raised it when the numbers were wrong. I had served the lab, and the lab had grown into part of me.

And yes—before spring came, I was approached.

The laboratory supervisor and the dekan called me in quietly. No ceremony. No applause. Just a folded paper, a nod, and a short line that made my hands sweat:

“You are being considered for a position as младший научный сотрудник.”

Junior Scientific Researcher.

That was it. My dream. To stay. To not just learn from the machine but become one of its gears—turning alongside those at the frontier of physics. The edge where theory bent toward experiment and reality had not yet decided its shape.

It meant permanence. Belonging. It meant I would not have to leave Bauman after graduation. I was becoming part of the future.

But before any of that could happen, summer came. And as with every summer before, I returned home—to Altai.

Except this time, I was not the barefoot boy running between haystacks or sketching wind patterns with red thread and notebook. I was a man now. I carried with me papers, instruments, and the silent confidence of someone who had passed through fire and calculation.

I was returning not as a visitor, but as a proud son of Altai.

My parents were older. I noticed it in the way my father set down his tools more slowly, in how my mother sat more often by the window with her tea cooling beside her. But their eyes lit up the same way they always had when they saw me coming down the path.

The fields were the same. The smells. The quiet. But something in me had changed.

I helped where I could. Fixed a radio. Rewired the chicken coop’s old fuse box. Sat with my father in the garage, handing him tools he didn’t need, just to stay in the rhythm of his company. My mother made dumplings I hadn’t tasted in years. She called me “our scientist,” though always with a laugh and not quite seriously.

That summer was the last time I would see them both together, just as they had always been.

I didn’t know it then. Maybe it’s better I didn’t.

But I remember every day of it like a mountain lake—cold, clear, and still.

After a week of home repairs, quiet meals, and unspoken pride, I packed a small bag and set out into the hills. Just me, a knife, bread, matches, and a battered field journal. I needed to feel the land again. I needed silence not found in dormitories or lecture halls. I needed wind that didn’t echo through buildings but through pine.

I followed no trail—just old memory. The slope behind the pasture still bore the faint trace of goat tracks. The creek still curved like a question mark where the soil had caved ten years ago. The rock outcrops stood like time had frozen them on purpose.

I slept near the same ridge where I had once overheard the singing men.

The forest greeted me like an old friend who asks no questions. Its language returned to me slowly: birdsong patterns, moss direction, the feel of dry stone before rain. I walked with no goal, listening—not for words, but for the rhythm beneath everything.

One morning I sat beside a narrow glacial stream, cold mist curling over my fingers as I dipped them in.

And I felt it.

Not magic. Not revelation.

Just… alignment.

As if something deep in me—strained from fluorescent lights, solder fumes, logarithmic exams, and the silent pressure of being noticed—finally found its breath again.

I could sense things I hadn’t since childhood: the strange geometry of trees when no one watches, the tension before a gust of wind, the invisible currents that birds ride without effort. The world had its own invisible system of feedback—fault lines not of earth, but of perception.

I stayed out there for three nights.

On the third, I dreamed of wires buried in roots, of stars pulsing in phase with the river, of machines made not of metal, but stone and song. I awoke before dawn, heart steady, sky violet, and I knew: I was ready to return.

But something had changed in me. Or perhaps… returned.

Now I understood.

I knew what needed changing in the lab—not just theory, but practice. How to tune instruments not for what we were taught to measure, but for what we had never thought to measure. How to build gauges for resonance, pressure, drift—subtle energies that escaped the neat lines of approved textbooks.

Where before I had copied the diagrams, now I saw past them.

And when I’ll return to Bauman, I’ll carrie the forest in my lungs—and the frequency of the mountains in my hands.

Chapter 11 — The Voice of the Field

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

So I returned to Bauman—not as a student anymore, but as a part of it.

I was no longer one of the many. I was now part of the scientific staff, formally recognized, with my name on rosters and responsibilities listed on walls. I had keys. I had tasks. I had a place not just to learn, but to teach.

They assigned me dual duties: to continue my laboratory work on precision instrumentation—and to assist in student laboratory instruction. I would now stand on the other side of the bench, helping others calibrate the same voltmeters, lasers, and resonance boxes I had once cleaned and aligned in silence.

It was an honor, yes. But also a test. A new rhythm. Authority is not the end of a journey; it is its reshaping.

Some students responded with curiosity. A few with boredom. Most followed the steps as written and moved on. They understood how to complete a lab—but not always why it mattered.

I didn’t blame them. The manuals weren’t written to inspire. The schedules left no room for questions that wandered too far from the curriculum. My job was to keep them on track, to mark results, to correct setups, and to issue quiet warnings when a careless wire or loose bolt threatened the integrity of the data.

I focused on what could be measured.

What could be improved.

What could be built.

Because even I—despite everything I’d learned—was still learning.

What I had brought back from Altai wasn’t magic.

It was discipline.

It was clarity.

It was something closer to premonition—a kind of feeling that came just before knowing. A subtle awareness that something wasn’t right with the setup, or that a measurement was about to drift, even before the data confirmed it.

I couldn’t explain it. But I trusted it. And little by little, I began to rely on it—not as a belief, but as a tool.

By the end of that year, I was no longer thinking like a student or an assistant.

I was beginning to think like a researcher.

Chapter 12 — Let Us Write a Dissertation

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

Two years into my official work at Bauman, the shift became undeniable.

I was no longer the quiet assistant in the corner, soldering cables and scribbling notes in the margins. I had made a name for myself—not through ambition, but through function. My devices worked. My measurements were clean. My setups did not fail.

Word spread.

Professors from neighboring departments started visiting my bench, asking for help with alignment, with calibration, with timing circuits that their graduate students couldn’t tame. And not just from Bauman—colleagues from MGU, Moscow State University, began appearing in my lab, asking if they could borrow or replicate some of the measurement instruments I had built.

I never advertised. The tools spoke for me.

Some were custom photodetector housings. Some were finely tuned delay lines, assembled from discarded Western parts with Soviet substitutes fitted by hand. Others were what they called “niche gages”—devices for tracking variables no one had thought to isolate before. I made them because I needed them.

And now others did too.

That was when the pressure began to mount—not from above, but within.

It was time.

Time to gather what I had done. To structure it. To defend it. Time to write a proper dissertation and move toward the Candidate of Science degree—the Soviet academic bridge between a Master and full Doctorate. Not everyone reached it. Many feared the process more than the math itself.

But for me, it felt inevitable. Not as a goal, but as a gravitational point I was already falling toward.

And so I began.

Not in haste. Not in glory.

But with quiet hands, late nights, and the same tools I had built for others—now turned on my own work.

My research circled around a problem that had been quietly growing in my notebooks for months: the behavior of magnetic fields within quantum-scale experimental configurations—especially the anomalies observed when measurement precision pushed beyond standard tolerances.

It wasn’t a theoretical pursuit in the abstract sense. I wasn’t trying to revise Maxwell or Einstein. But I had begun to notice something curious in the lab—something most dismissed as noise or artifact. When certain types of magnetic field sources were introduced into narrow geometric constraints—small cavities, split-ring resonators, or shielded vacuum chambers—the expected behavior of induced current or alignment would sometimes drift.

Not chaotically.

Not randomly.

Subtly.

Predictably.

But only when you were precise enough to see it.

The standard models of the time accounted for field strength, gradient, and induced resonance under classical electrodynamics. But my data hinted at a deeper interaction—an alignment disturbance, likely quantum in nature, that appeared when the field interacted with low-energy boundary conditions, especially when entangled with environmental constraints like shielding materials or residual thermal interference.

To simplify it for the dissertation board, I shaped my work around:

“Measurement-Driven Distortions in Magnetic Field Geometry Under Confined Quantum Conditions.”

That was the title.

Behind it, however, stood something more subtle—the interaction between observation, apparatus, and field behavior in conditions where classical physics no longer held absolute authority.

It was early work. Careful. Conservative in the writing.

But it held something.

And some on the board—especially the older theorists—noticed.

After a quiet discussion among my department head, the lab supervisor, and a senior theoretical advisor, I was called in and told simply:

“You have our добро. Proceed.”

That was all I needed.

The writing came easily—not because it was simple, but because I had already done the hard part. I wasn’t assembling a theory from borrowed texts. I was documenting a path I had already walked, device by device, adjustment by adjustment.

Half the dissertation wrote itself in the voice of my lab notes.

The other half came from the instruments themselves.

My previous years of experimentation—especially the fine calibration studies on confined magnetic drift, and the anomalous interference patterns observed in tightly shielded cavities—formed the spine of the work. The schematics I had drawn by hand, the testing logs I had triple-verified, and the tools I had built from scrap and genius—they were no longer improvised solutions. They were methodology.

Still, I didn’t rest on what I’d already done.

In that final year, I added a new set of experiments: using a narrow bore cryogenic tube, I demonstrated that certain resonance instabilities could be tuned—not eliminated—by introducing precisely timed pulsed magnetic fluctuations. It hinted at field memory—a controversial idea, whispered among fringe theorists but never formalized.

I didn’t claim discovery. I presented only what the data showed.

That restraint, I think, won respect.

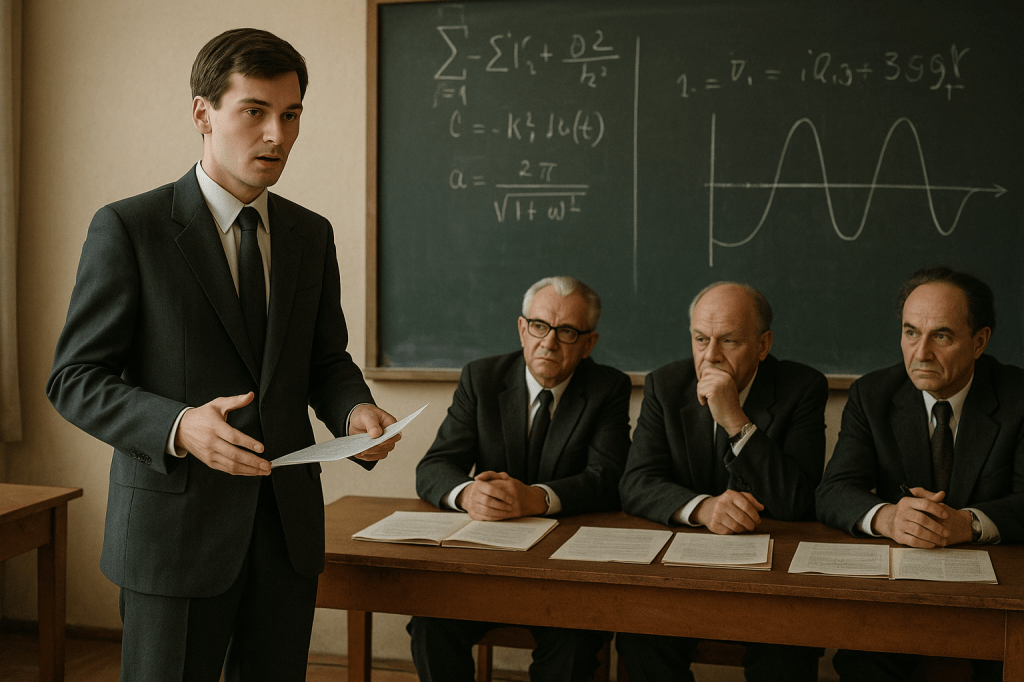

And so, near the end of that year, I stood before the academic board and defended my dissertation.

The room was quiet. My diagrams were crisp. My equations filled the blackboard behind me in chalk that never once squeaked.

There were questions—sharp ones. But no contempt.

One professor leaned forward halfway through and said, “It’s not elegant. But it works.”

I smiled. That was better than praise.

When the deliberation ended, they returned with sober faces, a stamped folder, and a single line:

“The degree of Candidate of Physical and Mathematical Sciences is hereby awarded.”

Just like that, it was done.

I had crossed another threshold.

Chapter 13 — The Corner of the Field

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

Still in my late twenties, I had become—unofficially—as independent in the laboratory as any full professor. My name didn’t carry the title Doctor yet, but it didn’t need to. At Bauman, everyone knew who handled the impossible measurements, who saw the anomalies others missed, and who built the tools to chase them down.

My direction was clear: fields, fine structure interactions, magnetic irregularities, quantum response to confinement. But more than that, I had become known for what I could build—precision instruments for those who demanded more than textbooks could provide.

By 1976, I no longer borrowed or improvised.

The procurement system worked for me now. The best parts—Japanese op-amps, German crystal timing modules, American analog feedback controllers—they found their way to my bench with little explanation. No one questioned it. Someone, somewhere had given the quiet order: let him work.

And so I did.

My corner of the laboratory had grown into a semi-autonomous zone—neatly arranged, highly sensitive, and always active. I designed my own circuit boards. My own cooling enclosures. I built things that didn’t exist in Soviet catalogues:

- Multistage resonance splitters for chasing field transitions inside vacuum chambers

- Quantum-aligned delay gates calibrated to femtosecond response

- Micro-response integrators capable of distinguishing background drift from coherent magnetic echo

Everything in my space served one purpose:

to detect and define what had never been measured before.

Not speculation. Not theory. Evidence.

That was the difference. Anyone could propose.

I could prove—or disprove.

People came from other institutes to consult. Professors, PhD candidates, even senior researchers. Some arrived proudly, others quietly. All left differently.

And occasionally, a man in uniform stood near the wall.

He never spoke. Never entered. He didn’t examine the equipment. He didn’t need to.

He was there to watch the visitors, not the work.

He saw who came in, how long they stayed, and whether they left with notes or without them. His eyes followed their movements like a silent checksum, a kind of human timestamp.

Eventually, I stopped wondering whether he was watching me, or watching over me.

Then one day, everything changed.

The man in the corridor didn’t appear that morning.

Instead, the Bauman KGB liaison—our curator, as we informally called him—arrived in person, flanked by two unfamiliar men and the head of our lab. There was no announcement, no paperwork, no formal summons. They simply walked into my corner like it belonged to them—and, in a way, it did.

The lab chief looked tense. But his voice remained measured.

“Comrade Malsteiff,” he said, “a new responsibility is being entrusted to you. A technical assignment in service of a classified defense project. You will not be alone—but you will be central.”

He said “responsibility.”

But what he meant was command.

I was to be transferred—temporarily—to a closed facility for a joint research program serving the Soviet military’s strategic field technology division. The specifics weren’t given. The message was clear: go, do your work, ask no questions.

One of the men behind the KGB officer handed me a sealed envelope. Another simply nodded. They didn’t speak.

The chief added:

“You may bring one assistant. The rest will be handled by the facility. The plane leaves tomorrow.”

I knew immediately who I would take.

Alina. A young lab assistant barely out of her studies, but with rare hands and sharper eyes. She had proven herself not only competent, but trustworthy. No curiosity where there shouldn’t be. No flattery. No fear of night work, chemical burns, or electrical noise. She knew how to see a waveform with her fingers before it even reached the screen.

When I told her, she nodded once. That was enough.

The next morning, we boarded a Yak-40 from a restricted hangar. No markings. No windows in the lounge. Just cold metal and military gray.

The aircraft groaned on takeoff, then surged forward like a whisper trying to become a roar. I sat with a clipboard and my case of calibration tools. Alina sat beside me, quiet, staring out at nothing.

No announcements. No stewardess. No map.

But what a plane.

If you’ve never flown faster than sound, you wouldn’t understand.

It’s not noise.

It’s the absence of it.

No thunder, no cinematic boom. Just the sudden sense that you’ve outrun your own echo. The world behind you is sealed off. The future ahead remains silent. And all around you—

Only the soft, continuous hiss

of the fuselage kissing air

at impossible speed.