Chapter 26 — The Conversation at Bauman

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

The return to Bauman was quiet.

No questions.

No ceremonies.

Only the stillness of heavy doors and long hallways, as if the building itself had agreed to forget what had happened.

Alina resumed her duties beside me. We said little.

But three days later, I was called to the chief scientific officer’s office.

When I entered, I saw him sitting behind his desk, hands folded, not unkind—but cautious. Beside him stood the KGB liaison—the same one who had watched my early work before Crimea. This time, he did not pretend disinterest.

The chief motioned to a chair.

“Please sit, Comrade Maltsev.”

I did.

A pause.

Then the officer spoke.

“We need to inform you—formally—that the individual involved in the… incident… has not recovered.”

I said nothing.

“He remains in critical condition. Neurological silence. He breathes, but nothing else.”

The room held its breath with him.

Then came the second layer:

“He was the nephew of a high-ranking official in the Ivanovo-Frankovskaya oblast party committee. KPSS.”

My stomach didn’t turn. It didn’t need to.

This was not a surprise.

Only a confirmation of why I was not being thanked. Why I was being watched, not celebrated.

“We are not accusing you,” the KGB man said calmly. “You gave instructions. You left the room. Your warning was on record.”

“But the situation is delicate,” the chief added. “And eyes are on us.”

I understood.

They weren’t warning me.

They were reminding me—

That my survival was conditional.

That memory was selective.

And that nothing is ever truly forgotten in Moscow.

“Your lab will continue,” the chief said. “Quietly. We recommend no new prototypes for the foreseeable future.”

The KGB man’s final line was almost friendly:

“History is kindest to those who do not write it.”

I nodded. I left.

But I didn’t feel free.

And the next morning, I was summoned again.

Same office. Same two faces.

But this time, the tone had changed.

The chief leaned forward.

“After some consideration, and coordination with northern authorities, we’ve decided it would be better—for everyone—if you took a field assignment.”

I didn’t answer. I waited.

“Bauman has been requested to assist the Kola Superdeep Borehole site. They’ve encountered… anomalies. Unusual data patterns. Equipment malfunctions. Signals they can’t interpret.”

The KGB man added, smoothly:

“You have practical skills. Especially with sensor design and field harmonics. We believe you’re the best candidate. And it will allow your work to continue… quietly.”

I understood immediately.

It was exile.

But with a lab coat.

The north. The deep drill.

A project surrounded by mystery and whispers.

An assignment no one asked for unless they were already buried by something else.

But they were right about one thing.

I did have the skills.

And whatever was happening there—was worth knowing.

I nodded once.

“When do I leave?”

Chapter 27 — The Descent Toward Kola

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

“Alina?” I asked.

The science chief glanced at the file in front of him.

“Unavailable. Reassigned temporarily.”

I didn’t press. I understood.

Too much history, too close to me.

Instead, they handed me a packet of names—assistants from the Kola technical crew. Engineers. Geophysicists. Some military support. People I didn’t know and hadn’t trained. But it didn’t matter.

“You’ll have help,” the KGB man said.

“Anything you need, just request. But act with discretion.”

He stood and walked to the window.

“You’ll be on a sealed manifest. No public record. Internal only.”

The chief added, softer:

“Take what you need from the lab. Instruments, notebooks, any designs from Crimea you wish to build upon. Once you’re there…”

He didn’t finish the sentence.

He didn’t need to.

Once I was there, I’d be alone.

Not punished.

Not erased.

Just sent downward—into something no one else wanted to touch.

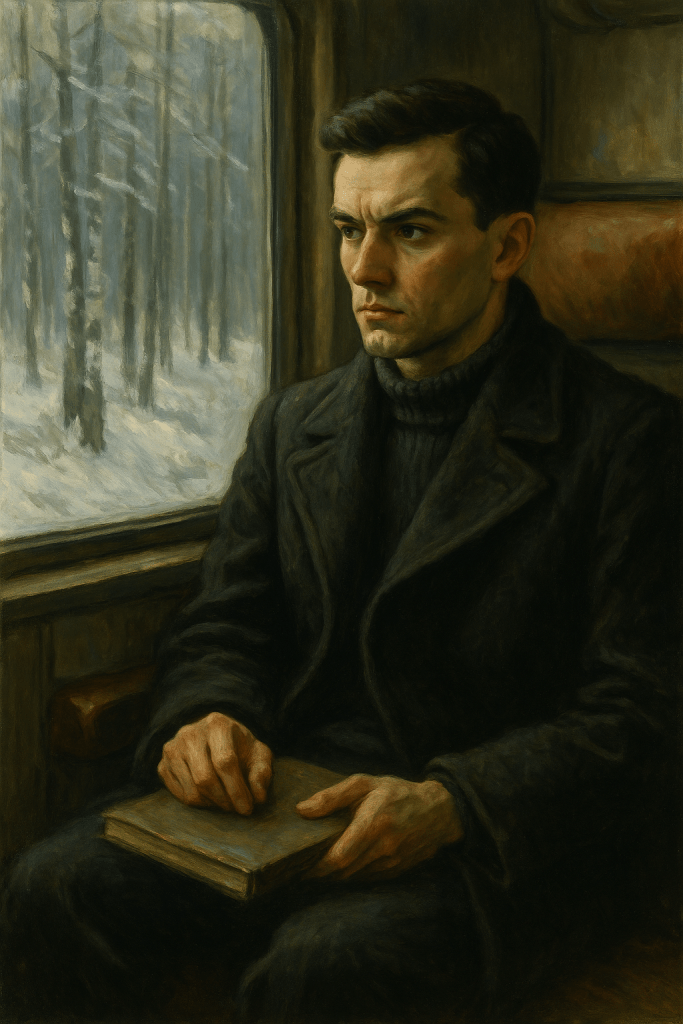

I didn’t board the flight they offered.

I told them I preferred the train.

They didn’t argue.

Maybe they understood.

Maybe they didn’t care.

Moscow to Murmansk is not a short journey by rail.

It winds. It waits. It watches.

But I needed the time.

Not for rest. For thinking.

I sat by the window, my notebooks stacked beside me, a simple canvas bag holding every tool I trusted—measuring probes, coil sketches, fragments of Crimea’s arrays.

The train was half-empty.

Engineers. Soldiers. Quiet men with bags too heavy for business, too light for war.

Nobody asked questions.

The trees outside changed slowly—from pine to larch, from wet earth to ice-hard permafrost. Towns grew further apart. Signals thinned. The silence stretched.

And I found myself watching not the landscape—but the reflections in the glass.

What exactly am I going north to meet?

What lives in the deep that our instruments are afraid to name?

I didn’t know.

But the further I went,

the more I felt it.

Not dread.

Not yet.

But something like…

inversion.

Like I wasn’t going down into the earth—

But the earth was rising to meet me.

The train rumbled northward, but my thoughts drifted farther back—not to Crimea, not to Moscow, but to Altai.

That night in the mountains.

The fire.

The song.

The shouting at dawn.

What changed in me?

I had called it an accident. A curiosity. A lingering resonance from something old. But now, as the birch trees blurred past the window, I began to wonder:

Was it a gift?

Or a mark?

An ability?

Or a fracture?

Something had been passed to me. I hadn’t earned it. I hadn’t asked for it.

But it came all the same.

A kind of attention—a tuning, not outward but inward.

I had called it pattern sensitivity. A field. An emotional antenna.

But what if it wasn’t new?

What if it was something prehistoric?

Not a technology—but a legacy.

A song, carried forward through chants and fires and initiations—not to explain the world, but to preserve something inside us. Some capacity modern life forgot how to name.

I thought of the old migrations.

The archaeogenetic maps.

The theories that many tribes who became Europe began in the Altai range.

What were they running from?

Or what did they carry with them that others wanted to silence?

I didn’t know.

But I knew:

That night,I didn’t take anything.

I wasn’t given anything.

I was simply the one most fit to receive it.

Not by magic.

Not by blood.

But because I was the best choice—

The mind most suited to carry it forward.

To hold it without losing myself.

To see the edge without falling.

And now, as the train rolled north into the gray silence of snow and iron,

I was bringing it with me—

Not as a burden.

But as a tool.

Because whatever was waiting at the bottom of that borehole…

It would not be met by fools.

Chapter 28 — Arrival at the Borehole

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

The train groaned into the Murmansk station beneath a pale, washed-out sky. The cold was immediate—not sharp, but saturating. The kind of cold that seeps into your bones before your skin notices.

A plain black Volga waited at the platform. No name held up. Just a man in a fur hat and a sealed envelope.

“To Kola,” he said. “They’re expecting you.”

We drove for hours along an empty road, past frozen forests and skeletal power lines. Wolves might have passed us in the woods. I wouldn’t have seen them.

And then, from a rise in the land—there it was.

The Kola Superdeep Borehole.

A structure that should not have looked ominous… but did.

The main tower rose like a forgotten missile silo, surrounded by support buildings half-buried in frost. Smoke curled from generators. The snow was streaked with rust where the earth had been disturbed.

But what struck me most was the silence.

Not dead silence.

But something more complex—like the land was listening to itself.

I was greeted by a man in a thick coat, name unreadable on his badge.

“We’re glad you came,” he said. “Some of our instruments are reading… things. But it’s not just noise. It’s too patterned. And the drills won’t hold frequency.”

I nodded, but my thoughts were already turning—backward, not forward.

What had the Nazis tried to find here?

It didn’t matter, really.

Whatever they were seeking in 1943—esoteric knowledge, “earth spirits”, subterranean gods—was born from madness and desperation. They came to places like this not to understand, but to possess. To take symbols and force them into weapons.

But the truth is, they couldn’t have understood what we know now. Not even close.

The work I was doing—sensor harmonics, emotional patterning, the early stirrings of a quantum field model—none of it was possible in their time.

They had no language for it.

No instruments.

No humility.

So whatever they thought they were hunting beneath the Earth, they couldn’t hear what I now began to sense:

A system.

A structure.

Not magic—

But something deeper than we’d ever defined.

Chapter 29 — The Team and the Threshold

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

We thought we were ready.

After the chaos of Kola, I arrived at the borehole site with a plan. Our team—assembled hastily but with conviction—brought everything we believed we needed to listen to the Earth’s voice again. Only this time, deliberately. Cleanly. Without incident.

We started with the basics: precision sensors, magnetometers, seismic filters, and calibrated reels of high-tensile cable. A stripped-down version of the Flux‑3 array. A secondary coil to catch faint magnetic interference. One cryo-thermometer jacket.

The snow groaned beneath the weight of our boots as I stepped out into the compound for my first proper day of work.

Steel stairs led down from the main barracks toward the staging yard—a maze of coiled cables, heavy equipment cases, makeshift sheds stitched together by tarps and hope. The smoke from the diesel generators didn’t rise. It spread low, as if the air itself had grown too thick to let anything escape.

The borehole was deeper than anything mankind had ever pierced. Over eleven kilometers—a wound in the Earth filled not with blood, but with signal.

And it was mine to listen to now.

The Team

Sergachev, the site director, a stern man with snow-white eyebrows and a Tatar’s sharp posture, assigned me to a special experimental unit. “You’re not drilling,” he said. “You’re listening. So I’ve given you quiet people.”

He wasn’t wrong.

- Dr. Irina Volkova, geophysicist. Late thirties, sharp-eyed, quietly cynical. Her specialty was seismic inversion modeling—mapping what you couldn’t see by listening to what reflected upward. She didn’t believe in ghosts—only unmeasured noise.

- Lev Petrov, a radio engineer from Leningrad, pale and wiry, with permanently cracked fingers and a nervous cough. He didn’t speak unless cursing, and even then, only to his soldering iron. He once repaired an array using a melted toothbrush handle and a sardine tin.

- Captain Mikhail Orlov, logistics. Ex-military, built like a granite wall, spoke like a man who had seen officers disappear and lived long enough to know when not to ask why. He found diesel, dry cables, and chocolate—all of which were in short supply.

There were others, rotating in and out. But we were the core.

Instruments Deployed

We set up our gear over two days, working between weather windows and equipment seizures.

- Flux‑3 Coil Array – my own invention, field-tested in Crimea. A spiraled stack of toroidal sensors designed to pick up pico-tesla magnetic shifts. Sensitive enough to detect the brainwave of a rabbit, if you could keep it still.

- CryoSpect 1 – a thermal-radiation spectrometer encased in liquid-nitrogen jackets. It tracked mid- to far-infrared emissions from deep strata, looking for non-thermal anomalies.

- Resonance Cavity Sensors – wide-bell microphones shaped like bronze bowls, lowered into the borehole. These weren’t for drill monitoring. They were there to listen. For what, we didn’t know. But by week’s end, we would.

Routine

- 0600 hrs: Scrape ice from housings. Lev swore in four languages. I recalibrated the coil array against the arctic cold.

- 0830 hrs: Irina downloaded readings to reel-to-reel tape. Data was plotted on acetate overlays taped to the mess-hall wall.

- 1200 hrs: Lunch—black bread, pickled herring, cabbage soup, and endless tea.

- 1300–1800 hrs: Lower the sensors into the mouth of the borehole to max depth, up to 100 meters. Log temperature, pressure, and flux by hand.

- Night shift: Lev and I huddled in the instrumentation van. The metal groaned. The readouts blinked. And together, we listened to the earth.

Early Observations

- Day 3: The Flux‑3 array registered nothing.

- Day 5: CryoSpect a mid-infrare no spike.

- Day 7: First resonance anomaly. A sustained harmonic at 17 Hz—too pure for mechanical origin. It echoed up the borehole like a chant.

Irina stared at the waveform. She turned the gain down. Then up.

She looked at me and said:

“That’s not from us.”

Chapter 30 — The Depth Without Echo

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

“No,” I said, after a long silence in the van.

“That’s not from us.”

Irina stared at the printout again, eyes narrowed, as if the waveform would confess something if she looked hard enough.

“Could be pipe resonance, but…” she trailed off. “It’s too stable. And it came back again at the exact depth. Twice.”

The readout from the 17 Hz harmonic sat between us on the desk, flanked by Lev’s half-melted oscilloscope and a coil of tape no one had labeled yet. The resonance was too clean. No tremor bleed. No frequency scatter. It wasn’t echo. It was presence.

And I felt it.

Not in my mind. In my gut.

The kind of feeling I used to get before thunderstorms in Altai—when the air stiffened and the trees braced without wind.

This wasn’t noise.

It was response.

And so I stood up and said:

“We need to recalibrate everything. We’re listening wrong.”

Lev grunted from the corner, soldering iron in one hand, flask in the other.

“You want to shift everything? At 7 kilometers? That’s suicide on a dry day.”

“We’re not shifting. We’re tuning.”

That night I didn’t sleep.

I sat with a pencil and a coil-bound notepad, scrawling cross-field overlays, resonance arcs, angular coupling diagrams. Somewhere past midnight I paused, hand frozen over the paper, because it had come to me—

Not flat.

Not linear.

Three-dimensional harmonic structure.

They’d been dropping cables straight down like fishing lines. But if the signal was spatial—spatially self-referencing—then we weren’t listening at the right angles.

We needed to answer in kind.

By dawn, I had the design sketched in graphite: a 3D resonator-emitter, something that could not just receive, but form a pattern of intent in the medium of Earth itself. A triaxial cage of copper loops, vibration-translating spokes, and a modulated frequency driver I would build from scratch.

It wasn’t communication in the way the military wanted.

It wasn’t language in any conventional sense.

But if the field we were touching had memory, rhythm, and shape—

Then maybe, just maybe, it had curiosity too.

“I’m ordering parts,” I told Orlov before breakfast.

“From Bauman. I want them flown in. I need custom capacitors, superconductive filaments, and three dozen ceramic cores.”

He didn’t argue.

He looked at me like he was trying to remember if I had gone mad already, or if this was the first sign.

“You’ll get what you need,” he said. “You always do.”

And I did.

Within ten days, the boxes began arriving. Each one marked “Academic Instruments – Bauman Internal Use”, with forms stamped in violet ink and signed by three different departments that didn’t exist on paper.

No one asked questions.

They didn’t need to.

Not because they believed in spirits.

We were Soviet scientists.

We didn’t speak of such things.

We dealt in pressure, signal, resonance, conductivity.

But still—

Something wasn’t lining up.

The readings weren’t stable. The drill motors fought invisible gradients. The harmonics returned at precisely regular intervals—from regions where there should have been nothing.

Not a voice.

Not a presence.

Just a pattern.

And if there was a pattern,

then it was our job to understand it.

Even if no one else saw it yet,

I did.

And I was building something that might answer it—not with faith,

but with physics.

Chapter 31 — The Mouth of the Earth

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

By the time we stood over the mouth of the borehole, the last pipe burr had been removed.

Twelve kilometers deep.

Nothing between us and the center of the Earth but time and unknown pressure.

And when I stepped near the lip, I felt it—not with my skin, but in the strange tuning of my body. A vibration.

Faint.

Wide.

Real.

It wasn’t supernatural.

It wasn’t fear.

It was signal—not from above, but rising from below.

Some of the workers felt something too, though they would never say it that way.

Roustabouts from Arkhangelsk and Komi, ex-submarine electricians—they drifted near the edge of the shaft as if pulled by instinct.

One muttered something about hearing whispers.

Another simply stared, then walked away, as if he’d remembered something he didn’t want to.

But what they sensed in tension, I felt in structure.

This wasn’t imagination.

It was a field.

Born not of mysticism, but of physics—frequencies embedded in old strata and flowing upward like an ancient pulse looking for a match.

And I was here to give it one.

We brought out the reels.

Not one, but two:

- The first sat directly over the borehole, unspooling the titanium-reinforced descent cable—braided, frost-hardened, engineered to survive pressures we still hadn’t defined.

- The second reel—positioned beside it—fed out the signal spine: a layered braid of fiber optics, power lines, and signal relays, triple-insulated and shielded with copper mesh.

The system wasn’t automated.

It was manual.

Deliberate.

Lev and I worked side by side in the freezing wind, joining each segment by hand—meter by meter. Every length was connected with clamp sleeves, soldered terminals, and sealed joints. Sometimes I held the cables in my teeth while he wrapped insulation around the fiber splice.

It wasn’t pretty.

But it worked.

Then came the resonator-emitter.

Our prototype.

Not just an instrument—but a presence. A geometric construction of concentric rings and tensioned filaments, balanced for asymmetry, designed to receive by being shaped.

I gave the nod.

“Begin descent.”

And they obeyed—not from fear or order, but because they knew it was my design, my signal, my test.

The cable fed down slowly, hand over hand, wheel over wheel—through one reel, then another. We met in the middle, meter by meter, hands raw in the cold, locking wires together, joining fiber optics to copper, one length at a time.

And as we lowered the array into the dark, the vibration began.

Not from the device, not from the ground—but from the space around it.

It was a braided, vibrating coil of twisted field energy—hissing skyward like a serpent uncoiling, reaching into space.

No one else heard it that way.

But I did.

And in that moment, I knew:

We had discovered something deep and alive in tension.

And I knew—

It was something important.

Not just for my research,

Not just for Bauman or the project—

But for Earth.

For humanity.

I didn’t know why.

Not yet.

But I could feel it.

Like a pressure behind the eyes of thought.

Like something ancient finally noticed, and waited for us to speak correctly.

It would take me years to understand what we had built.

What we had awakened.

And what we had nearly lost.

And the silence around us was no longer empty.

It was listening.

Chapter 32 — The Echo Pattern

Edited and prepared for publication by his friend and colleague, Professor Rook

It took us two days and nights to lower the full array.

We worked in shifts—two crews, alternating between fevered labor and brief warmth. The Arctic air knifed through canvas, but we had tea steeped strong with cognac, and determination stronger than cold.

By the time the resonator-emitter reached seven kilometers, the readings began to shift.

Not just echoes. Not just noise.

The array began to vibrate in structure.

Three-dimensional harmonics appeared in the data—waveforms layered not just in amplitude, but in topology. Some of it looked like folded frequencies, impossible under classical constraints. Other readings came in as if they belonged to a space not entirely inside ours.

Were we measuring a new zone of the Earth? Or were we witnessing how our device responded in a realm where no instrument had ever operated before?

We pushed deeper.

By eleven kilometers, the field patterns thinned. The structure became less dense, less organized—no longer spears, but clouds. Irina called it a collapse of pattern coherence. Lev said the instruments were just losing signal. I said nothing.

I was in the tent-hut, eyes on the screen.

When the heat sensors tripped, I knew we’d hit the threshold.

Temperatures reached critical levels for our instrument payload. I ordered a halt.

“This is it. No deeper.”

Instead, we reversed strategy.

We initiated our first emission cycle.

The emitter, still suspended in the shaft, was switched from passive to active. It began releasing calibrated vibration pulses—gentle resonant triggers designed to agitate the Earth’s field within the shaft itself.

Then we began the slow withdrawal.

As we drew the array upward, we pulsed it.

Recorded everything.

At first, there was almost nothing—dull resonance, scattered echoes.

But the higher we climbed, the sharper the reaction became.

It was as if the field grew more sensitive to the intrusion.

Or more disturbed.

Each pulse was answered more aggressively.

By the time we passed seven kilometers, it happened:

A return wave.

Not just vibration—a scream.

Not audible through speakers. Not logged on screen.

But I felt it.

Like a nail driven straight from the base of my spine to my skull. Like my soul split open.

My knees buckled. The instruments swam.

I collapsed.

The others stabilized me. They hadn’t felt what I had. To them it was just another spike.

But I knew.

Something had been torn.

When I came to, I checked the instruments.

The system was intact. All power routed. No breaks. No shorts.

But there was nothing.

No field.

No echo.

No hum.

Silence.

All the way to eleven kilometers.

Something had gone out.

We retrieved the system in half a day. The drill team returned. They resumed operation.

Then it happened.

When they reached twelve kilometers, a sudden seismic impulse crushed their drill assembly. The pipe fractured.

Only seven kilometers were recovered.

The rest was gone.

There was blame. There were accusations.

Bauman was contacted.

But they didn’t come to defend me.

“You’re potato too hot to hold to,” one of them said. “But we know someone who’s still interested.”

And that was how I found myself reassigned—

To a facility in the Ural Mountains, deep in Sverdlovsk region.

Still listening.

But now underground.

Before we all separated, we drank vodka and wrestled bears.

Ha, ha, haaa! Bearded friends—not like American horny rednecks, no—just drunk comrades in the cold snow, laughing into the frost.